A Mental Model from Evolutionary Biology That Will Change How You Work

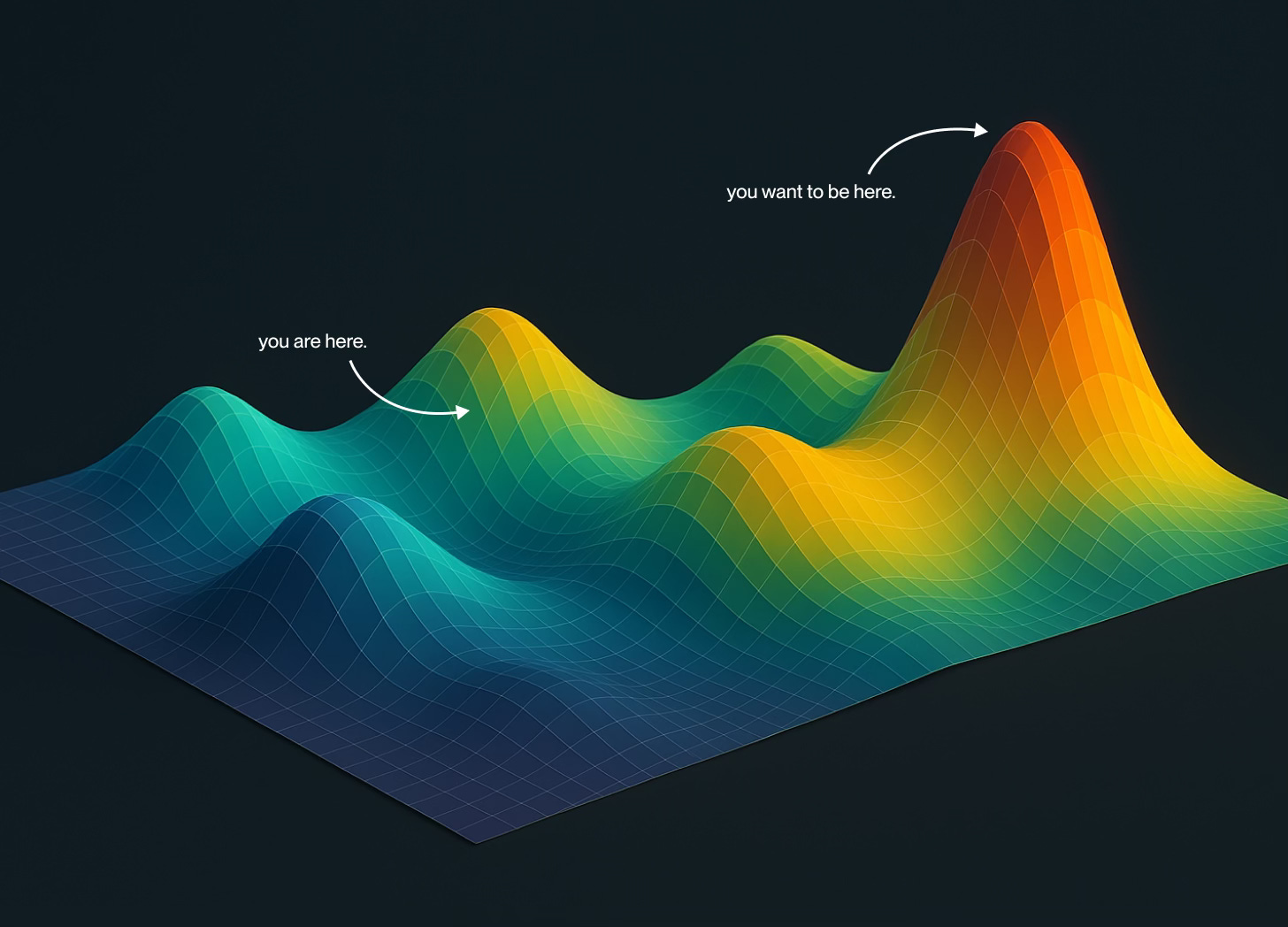

Borrowed from evolutionary theory, the fitness landscape helps you understand progress, risk, and adaptation by thinking in terrain, not timelines.

Some teams sprint confidently in the wrong direction.

Others stay put, optimizing something that no longer matters.

And most don’t realize the ground is shifting beneath them until it’s too late.

Strategy often pretends to be linear. We create roadmaps. We build backlogs. We schedule launches. But beneath it all, what we’re really doing, whether we’re designing a product, running a company, or writing a song, is trying to navigate an invisible landscape. Peaks of success. Valleys of failure. And no map that stays accurate for long.

That’s why now, I try to think in terrain, not timelines.

What Is a Fitness Landscape?

The concept comes from evolutionary biology. In the 1930s, geneticist Sewall Wright introduced the idea of a fitness landscape to explain how organisms adapt over time.

Imagine a 3D landscape. Each point on the surface represents a different genetic configuration. The higher the elevation, the more “fit” the organism, better adapted to survive and reproduce. Over generations, populations move across this terrain, ideally climbing toward higher ground. But sometimes, they get stuck on local peaks: configurations that are good, but not great. Reaching a better peak might require first descending into a valley.

Later, economist Eric Beinhocker borrowed the idea and brought it into the world of business and economics. In his version, fitness isn’t about biology, it’s about strategy.

A product, team, or business model exists somewhere on a fitness landscape, shaped by decisions: pricing, design, messaging, technology, structure. And fitness, in this context, could mean growth, profitability, relevance, adoption, whatever matters most in your market.

Importantly: the terrain is not fixed. It moves. Customer expectations evolve. Competitors launch. Technologies shift. What was once a peak may slowly erode, and a feature you polished to perfection might lose all relevance overnight.

How the Terrain Shifts

You don’t always realize it right away. Sometimes you’re just working harder, but it’s not landing like it used to.

Take Stack Overflow. For years, it was the go-to destination for developer answers. Search a question, compare responses, upvote the best. Then ChatGPT came out. Users didn’t want community-filtered information anymore, they wanted instant, personalized, well-formatted answers. Stack Overflow didn’t do anything wrong. But the terrain shifted. The fitness dropped. The model that once felt irreplaceable suddenly felt slow.

Or think about a subtle UX change. If Instagram took the “Post” button that’s in the tab bar and buried it deep in a settings menu, the core product wouldn’t change, but engagement would plummet. One tiny move could send the product tumbling off a peak.

You can climb. You can slide. And sometimes, you stay still while the terrain shifts beneath you.

Optimization vs. Exploration

The model also captures something many product teams feel but rarely name: the tension between optimizing and exploring.

Optimization is safe. You refine what’s already working. You make it faster, cleaner, easier. It’s hill climbing: local, focused, and incremental.

But sometimes, you’ve maxed out your current hill. And the only way to reach a better one is to jump. Try something riskier. Explore an adjacent space. Maybe it works. Maybe it doesn’t. But staying put guarantees you’ll never find out.

Most teams over-optimize. The best ones know how to switch modes, when to double down, when to zoom out, and when to leap.

Seeing Through the Landscape Lens

I used to treat product problems like puzzles. Ask the right questions, get the right answer. But strategy isn’t mechanical. It’s environmental. Now I try to see the map under my feet.

When a product feels stuck - not broken, but misaligned - I ask: are we climbing, or are we circling? Are we on the right peak, or just the nearest one?

I’ve definitely gotten stuck optimizing something that no longer mattered. At one point, I had a team refining a feature that showed clear signs of user drop-off. We told ourselves it was a UX issue, or maybe a messaging problem. The truth was simpler: the feature wasn’t valuable anymore. We were just emotionally and politically invested in it. And I was too slow to admit that. The landscape had shifted, but I kept my head down.

That’s the uncomfortable power of this model. Sometimes it doesn’t point to a next move, it just shows you that you’re on the wrong hill.

So I try to stay open. What’s changing? What are users doing differently? What have competitors stopped doing - or started? What assumptions are we protecting? And if we had no history, what would we build next?

The terrain doesn’t offer clean answers. But the questions it provokes are the right ones.

Signals the Landscape Is Moving

There’s no radar for this, but here are signs I look for:

Users start working around your product in odd ways

Net Promoter Score (NPS) holds steady, but growth softens

(NPS is a measure of how likely users are to recommend your product)Competitors reframe what success looks like

Your roadmap feels packed, but somehow irrelevant

The things that used to feel sharp now feel flat

None of these are failure. They’re fog. And fog usually means you’re not on a peak anymore.

This Applies to Careers, Too

The metaphor works beyond product and strategy. It applies to people.

The skills you’ve developed, the role you hold, the way you work — all of it places you somewhere on a personal landscape. A local peak, maybe. But not always the best one.

Sometimes, what looks like a lateral move, or even a step back, is just a way to find better terrain.

Climbing isn’t always upward. Sometimes it’s sideways. Sometimes it’s a controlled fall toward something better.

Entrepreneurs feel this landscape shift all the time.

Think about Meta. In 2021, they rebranded from Facebook and went all-in on the metaverse, betting big that it would define the next era of computing.

Then ChatGPT happened.

Overnight, attention, talent, and capital shifted toward AI. Meta responded fast. They pivoted hard toward LLMs, released Llama, and refocused their roadmap around AI infrastructure, not virtual worlds.

They didn’t fail. They adjusted. The terrain changed, and they moved with it.

Sometimes the most important thing you can do as a founder isn’t to push harder - it’s to look up, recognize the landscape has shifted, and pick a better hill to climb.

Final Thought

What I love about the fitness landscape model is that it doesn’t give you a playbook. It gives you perspective.

It helps explain why things feel stuck when they shouldn’t. Why good strategies can go stale. Why being right last year doesn’t guarantee relevance this year.

It nudges you to question momentum. To challenge comfort. To stay alert.

Because even if you’re standing still, the terrain isn’t. There is no neutral, only forward or reverse.

Think in terrain, not timelines.

Tomorrow, I’ll share three AI prompts I use to help me kickstart exploration - whether I’m rethinking a roadmap, escaping a local peak, or just trying to generate smarter ideas when the next move isn’t obvious.

Each one is designed to help you apply the fitness landscape lens in real, practical ways.